Фолк

Peter Waksman. DID GLOOSKAP KILL THE DRAGON ON THE KENNEBEC?

ROSLYN STRONG

© Peter Waksman,

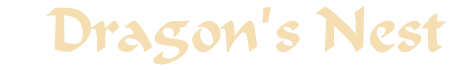

Figure 1. Rubbing of the "dragon" petroglyph |

Figure 2. Rock in the Kennebec River, Embden, Maine |

The following is a revised version of a slide presentation I gave at a

NEARA meeting a number of years ago. I have accumulated so many

fascinating pieces of reference that the whole subject should really be in two

parts, so I will focus here on the dragon legends and in a future article will

dwell more on the mythology of the other petroglyphs, such as thunderbirds.

This whole subject began for me at least eight years ago when George Carter

wrote in his column "Before Columbus" in the Ellsworth American that only Celtic

dragons had arrows on their tails. The dragon petroglyph [Fig. 1]

is on a large rock [Fig. 2] projecting into the Kennebec river in the

town of Embden, which is close to Solon, in central Maine. It is just

downstream from the rapids, and before the water level was raised by dams, would

have been a logical place to put in after a portage. The "dragon" is one of over

a hundred petroglyphs which includes many diverse subjects - there are quite a

few canoes, animals of various kinds, human and ‘thunderbird’ figures.

They were obviously done over a long period of time since there are many layers

and the early ones are fainter. They are all pecked or ‘dinted’ which is

the term used by archaeologists. The styles and technique seem to be

related to the petroglyphs at Peterborough, Ontario, which in turn appear to be

similar to those in Bohuslan, Sweden. Of course both of these conjectures

are not accepted by academia. The location is significant, directly across

the river from a campground that has been dug by state archaeologists and

produced artifacts in great quantities from many different periods, some very

old. There is another prehistoric site just a few miles upriver on the

same side as the petroglyphs. Note that this is a really good dragon - a

horse type head with horns, two sets of legs and a clear arrow at the end of the

tail.

Figure 3. The Welsh Dragon

I was eager to find the connection George hinted at, so on a trip to Scotland in 1987, I kept my eyes open for arrow-tailed dragons. Sure enough, only Celtic dragons had arrows on their tails! Oriental dragons generally have forked tails, but never arrows. Wales [Fig. 3] has the dragon as its emblem, and it is also the coat of arms of the city of London. As I did more and more research, I was led along many different paths, although I was hard put to find early clues to the origin of the arrows or even of the popularity of the dragon.

John Michell, in View Over Atlantis (1969), was one of the first to talk about geomancy, dragon lines and ley lines. He says, "In every continent of the world, the dragon chiefly represents the principle of fertility. The creation of the earth and the appearance of life came about as a result of a combination of the elements. The first living cell was born out of the earth, fertilized from the sky by wind and water. From this union of yin and yang sprang the seed which produced the dragon. Every year the same process takes place". He observed that the practice of Feng Shui in China contributed to the harmony of the landscape and the people in ancient times and that geomancy had been practiced in ancient Britain. "The places associated with the dragon legend, the nerve centers of seasonal fertility, appear always to coincide with sites of ancient sanctity". There are dragon hills in England, supposedly the dragon wrapped his tail around them and on some the grass will not grow on the top. The Uffington White Horse [Fig. 4] is carved into the chalk and originally represented a dragon. Just below it is a round hill with a flat, bare top.

Figure 4. The Uffington White Horse

The dragon came to represent evil in later Christian symbolism and was of course vanquished by the pure in heart – saints George, Michael, Margaret, Sylvester and Martha are all dragon slayers. I discovered another direction in a 9th century miniature [Fig. 5] with an arrow-tailed dragon banner in a Codex from the monastery of St. Gall in Switzerland. It seems that these were windsocks, used since Roman times to produce frightening noises in battle. St. Gall came from the monastery of Bangor in Ireland with St. Columban and twelve monks in the 6th century - another Celtic connection! They founded monasteries in Burgundy and Lombardy on their way to Italy where Columban founded Bobbio. There are mystical tales of St. Gall communicating with demons and animals — commanding bears to help carry wood to build the monastery, and he could talk with the water sprites. Could he have chosen the location because it was at the center of a powerful earth energy?

Figure 5. From the 9th century "Codex Aureus".

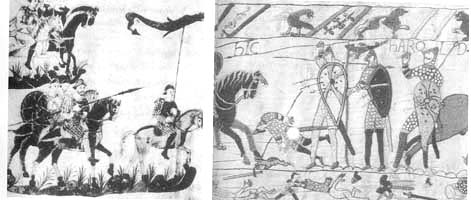

Figure 6. Section of the Bayeaux Tapestry

A dragon banner from the Bayeux tapestry depicts the death of King Harald

Godwinson. [Fig.6] His dragon banner is being crushed under the horse’s

hoof.

It doesn’t have an arrow, but is identified as a dragon. Mythology of all ages is rich in dragon lore. In Carnac (Brittany) during the 19th century, Roman Catholic priests would walk between the rows of menhirs on Palm Sunday, carrying holy water, an unlighted censor, a cross and a dragon on a pole. "The sacred fire in the dragon’s mouth brings to mind the holy fire kept perpetually burning on the altars of the children of the sun" (comment by an antiquarian who concluded that he had witnessed vestiges of an ancient ophite ritual going back thousands of years).

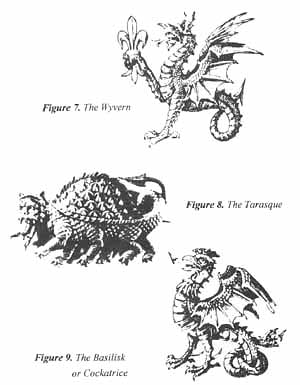

Other arrow tailed creatures led to weird tales of mythical beasts such as the Wyvern [Fig. 7] and the Tarasque, [Fig. 8] which is the creature tamed by St. Martha in France. This monster was described as half fish, half animal with great wings. He was rumored to have come from Galatia, the result of a union between Leviathan, the biblical water dragon, and the Onager, a ferocious -fire spewing beast. He menaced the whole countryside, slaying all travelers and sinking all boats. St. Martha came upon him in the act of devouring a man; she sprinkled him with holy water and held up a crucifix before him. He became meek as a lamb and allowed her to lead him by her girdle, but the townspeople finally killed him. They took the name Tarascon in memory of the event.

Figure 10. Basilisk on the reproduction of a 17th century card (symbol of Basel)

The Basilisk or Cockatrice [Fig. 9] is always arrow-tailed and has a multitude of esoteric connotations – it is hatched by a serpent from a cock’s egg and its glance and breath are fatal. It is usually evil, but here it is on a reproduction of a 17th century card from Basel [Fig. 10] where it is their symbol and from which the city takes its name. The story of the Cockatrice of Saffron Walden is typical of the alchemical implications. It killed many people by its glance, then a favored knight made himself a coat of "Christal Glass" and killed it. In memory his sword was hung up as well as an effigy in brass of the cockatrice, but it was taken down and broken in pieces as a monument to superstition. The alchemical [Fig. 11] overtones suggest that mixed or impure elements disintegrate on being brought into contact with what is refined.

Figure 11. "The dragon does not die unless itis killed by its sister and brother, Sol and Luna."

THE ORIGIN OF DRAGON LEGENDS

While dragon myths are found world wide, there is some speculation that an

origin can be traced to the near east in the area of Mesopotamia. The

Sumerians in the 5th millenium inhabited a country with many rivers and swamps

that did contain a form of crocodile. Their most important god was Enlil,

who started life as a river god, but was promoted to dry land and the upper

world. The serpent, or dragon, Zu stole the tablets worn by Enlil on his breast,

on which were set out the laws governing the universe. On Enlil’s orders,

Zu was slain by the sun god Ninurta, who thus set the precedent for sun gods who

battle with dragons.

Although most people today associate the dragon with fire, his primeval

element is water, whether the sea, rivers, lakes or rain clouds. Even in

deserts dragons lurk in the bottom of wells. There is little doubt that

the word "dragon" is derived from an ancient Greek word meaning "to see".

Its glance is searching, baleful and usually fatal.

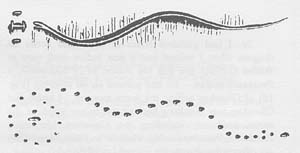

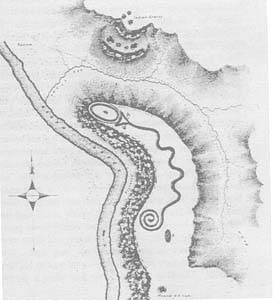

Figure 12. Serpent Mound in Iowa

I have accumulated a lot of dragon lore, but found almost none in North America, which makes our Maine dragon seem more important. There is quite a bit of serpent lore, [Fig. 12] there are many serpent mounds, including the most famous one in Ohio. [Fig. 13] It is a most impressive, very powerful place.

Figure 13. Great Serpent Mound, Adams County, Ohio

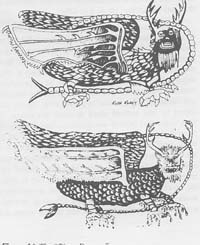

Mention American dragons and the ‘Piasa Dragon’ [Fig.14] on the Missisippi at Alton, Illinois immediately comes to mind. There were two figures high on the bluffs but they disappeared well before 1800. According to some, the Indians regarded it as a bad place and they shot arrows at it, then frontiersmen came along and did the same with their guns. Others say it was a sort of offering. There are legends among the Miamis about the monster coming to help them in battles with their enemies. These and other drawings were done after 1820 when none of the artists had even seen it. I researched it thoroughly and went back to the original source, which was Father Marquette in the mid 1600s. He described them thus: "They are as large as a calf. They have horns on their heads like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body covered with scales, and so long a tail that it winds all around the body, passing above the head and going back between the legs ending in a fish’s tail. Green, red and black are the three colors." A few other travelers in the 1600s gave slightly different descriptions, but all agree there were painted figures on the bluff.

Figure 14. The "Piasa Dragon"

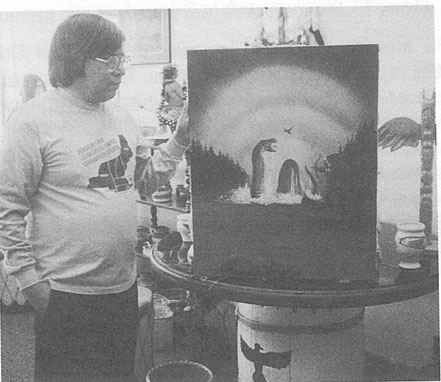

So, I had gathered boxes of notes and books on dragons when I walked into a new Indian craft shop in Belfast (Maine) and met the owner, Mike Sockalexis, a Penobscot Indian. He had painted an oil painting [Fig. 16] of Glooskap killing the water monster. I knew that Glooskap was a culture hero of the Indian tribes of the entire northeast, including the Canadian Maritimes: Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Mic Mac. They are often referred to as the Abenaki or Wabanaki.

Figure 16. Mike Sockalexis with his painting of Glooskap slaying the water monster

Mike showed me his copy of a book written by an ancestor of his in 1893, Joseph Nicolar’s Life and Traditions of the Red Man. Nicolar lived on the Penobscot Reservation on Indian Island near Old Town and was an important person in his tribe as well as a representative to the State for a time. He died in 1894.

I was astounded to hear Mike tell me the story - Glooskap always worked to make life better for his people and of course had magical powers. As he returned to his people by way of the sea, he found the waters foul and stagnant, with no breeze. This was because a dreadful serpent lived in these waters. As he approached the monster, it raised its head and ran out his fire-like tongue; and Glooskap knew he had to get rid of it. As the serpent reared up and seemed about to crush the canoe, ‘May-May’ — the Red-headed woodpecker — flew between them, lit on the end of the canoe and told him to shoot the arrow at the smallest part of the reptile’s body. Glooskap tried, but the arrow rebounded. Each time he shot at the tail, but nothing happened; each time May-May picked up the arrow and brought it back to him, telling him to aim near the tip of the tail. Still no luck. On the seventh try (and seven figures in so many of the Glooskap stories) the woodpecker flew ahead to show him exactly where to aim. This time it was successful, the beast writhed and thrashed and died. The water was bloody but began to clear and the breeze blew gently. In gratitude, Glooskap dipped his arrow in the bloody water and made the mark of an arrow on May May’s head and it is there to this day.

So - here was an exciting connection to a water monster and an arrow in a Native American tradition. I began reading Nicolar’s book, and then a few other collections of Glooskap stories, but was puzzled by the differences. Most of the others were collected by white men, Leland in 1884, then others including Spence, Beck and Frank Speck into the 1940s. They all had Indian informants, but the emphasis of these stories was on trickery, shape changing, animal stories. The title of Beck’s book is Glooskap the Liar! I was especially puzzled by the fact that all of the authors after 1900 certainly had access to Nicolar’s book. I visited my friend Eunice Bauman-Nelson, who is a Ph.D. in Anthropology, a member of the Penobscot Tribe and a long time NEARA member. She now lives on Indian Island, where she lived as a child. She remembers the authors and anthropologists coming to question the old men of the tribe and when the "anthros" left, the old men would laugh. They had embellished some of the tales with sexual connotations which never appeared in the real traditions because this seemed to be what was wanted. The white investigators most appreciated the stories that exaggerated trickery. Eunice feels that Nicolar’s book is much closer to the true tradition.

Nicolar’s book is so different. Not a collection of individual stories, it begins with a lovely creation story, some of which may have been influenced by missionaries, but full of basic events. Glooskap has the task of making the world better for mankind to live in, teaching them how to make fire, build canoes and other skills. He chips thousands of stone arrows, which the people use, but not until much later does he teach them how to make them. Glooskap decided the large wild animals were a threat to man and requested most of them to make themselves smaller as an accommodation to mankind. Most of them did, including a giant beaver (and in recent years the remains of a giant beaver have been found). However the mammoth refuses. Nicolar calls him ‘Par-sar-do-kep-piart’ and describes him: "his back was the shape of the half moon with a very small head for the body, with large but thin ears hanging down each side of his head; eyes and mouth small and the upper lip so long he could reach out with it seven paces and up among the branches of the trees; and there were two long horns on each side of his long lip". The mammoth was very arrogant because he was so big and powerful. Glooskap predicted that that when a greater power finished its work, there would be no more of his kind. A voice then spoke to Glooskap warning him to leave, there would be a roaring of the heavens to drown the howls of the mammoth. There was much lightening and then a great calm and the northern lights began to dance. Glooskap went about another mission, clearing obstructions in the water and as he returned, he found the waters foul because ‘there had been a great calm over the sea following the destruction of the mammoth and the dancing of the Northern Lights’. So these two things are tied together, and yet I find no other author or anthropologist has followed up on this.

I searched for any mention of a dragon or even similar water monsters in Indian legends and found almost nothing. The closest also comes from the Wabanaki, sometimes in the Glooskap stories. There is a small worm only a few inches long with horns, called the Weewilimecq. It can transform itself into a variety of larger serpents and some tales tell of specific Penobscot shamans who changed themselves into the Weewilimecq to battle with other shamans. The horns also have magical powers and this leads to other stories of serpent’s horns being valued in other cultures.

Mike Sockalexis gave a slide presentation at the NEARA meeting in the spring of ‘96, "A Spiritual Interpretation of the Petroglyphs of Embden, Maine". We are indeed fortunate to have the insight and advice of Native Americans in our region and look forward to further cooperation. The Embden petroglyphs are one of two major groups in Maine: the other is in downeast Maine near Machiasport. They must be over 2000 years old since they were carved when the shoreline was lower. They are now under water except at very low tide. Some of the designs are somewhat similar to those on the Kennebec, and others are so worn that they are open to a variety of interpretations. I hope to gather material from both sites for another Journal article in the near future.

Note 1.There are many variation in spelling: Glooscap, Gluscap, Gluscabe, Klose-kur-beh (Nicolar’s spelling).

Note 2. It is most interesting that the petroglyphs are located near the conjunction of the 45th parallel and the Kennebec. This is the northernmost point on Map 6, (Grants by "Council for New England") of Morse Payne's article in the NEARA Journal Vol. XXXI, No 2, page 93. We intend to pursue a possible connection.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Beck, Horace P

1966 Gluskap the Liar & Other Indian Tales

The Bond Wheelwright Co., Freeport, ME. - Bernstein, David J.

1986 The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry,

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London - Hoult, Janet

1987 Dragons, Their History & Symbolism. Gothic Image Publications, Glastonbury, England - Huxley, Francis

1979 The Dragon. Thames and Hudson, London. - Newman, Paul

1979 The Hill of the Dragon, An enquery into the nature of dragon legends. Kingsmead Press, Bath, England - Leland, Charles G.

1884 The Algonquin Legends of New England

Houghton, Mifflin & Co. Boston - Michell, John

1969 The View Over Atlantis. Ballantine Books, New York - Nicolar, Joseph

1893 The Life and Traditions of the Red Man. Reprint 1979 Saint Annes Point Press, Fredericton, N.B.

The Piasa

Pamphlet published by the Alton-Godfrey Rotary Club, Alton, IL - Ray, Roger

1987 The Embden, Maine Petroglyphs. Maine Historical Society Quarterly, Vol.. 27, No.1 Summer, 1987

© Peter Waksman,